2. Conceptual framework for measuring trade in digitised products

The scope of this study is quite broad. We will look into digital intermediation itself but also certain specific activities facilitated by digital intermediation. We will better examine the estimations for characteristic digital products such as database services, but sale of goods via e-commerce is also in scope of this study.

Wat is digital trade?

Digital trade, of course, is not completely new. As digitally enabled transactions in the purchase of goods and services alike have been part of the economic reality for decades. The issues raised by these digitally enabled transactions are the same or similar to those raised by non-digital transactions. This is because digital trade is not just about digitally delivered services, it is much broader. The increase in digital trade has effect on or is a result of changes in the entire supply chain of goods and services due to growing digital connectivity.

Digital trade is all trade that is digitally ordered and/or digitally delivered (OECD, 2019a).

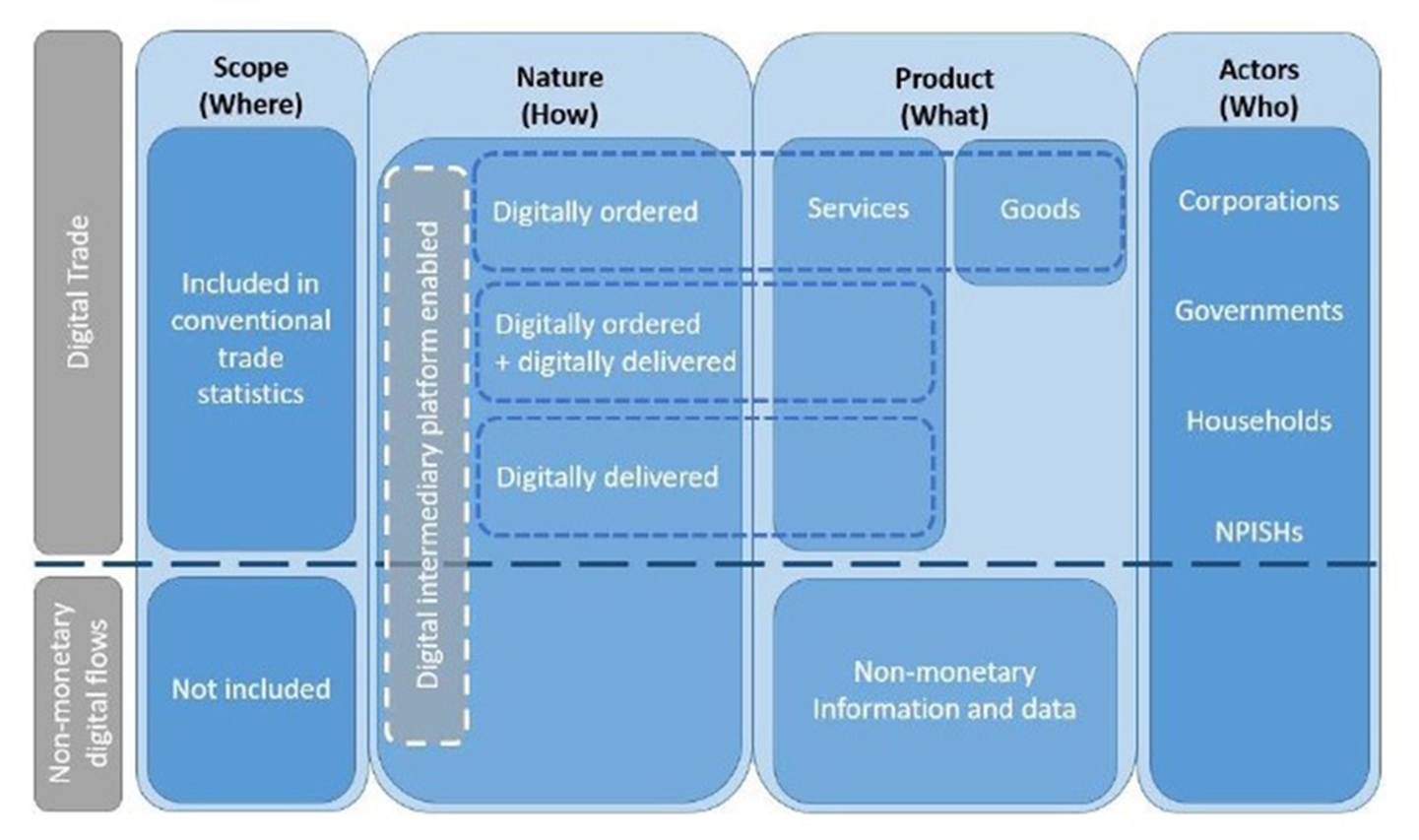

Due to the scale of transactions and the emergence of new (and often disruptive) players and business models, production processes and industries are being transformed. The scope of this transformation transcends the industries that were previously affected by globalisation (OECD, 2019b). Following the methodological guidance of the OECD “Handbook on Measuring digital trade” (see Figure 2.1 below) we try to supplement the knowledge on these transformations by looking into several goods and services that are digitally ordered and digitally delivered.

2.1 The conceptual framework for digital trade

Source: OECD

Digital intermediation

One of the eye-catching new business models due to increased digitalisation are online platforms. These days they are dominantly present in the market and are significantly influencing our economy. The era of so-called “Digital Disruptive Intermediaries” (DDI) has begun. In their research, Riemer et al. (2015) state that “DDIs approach markets as a matter of information management rather than traditional resource deployment and exploitation”. Information is key. To be successful, online platforms have to use and organise the user’s data to increase their profit from supply of services. Following the classification of the DDI presented in the research done by Riemer et al. (2015), digital intermediaries like Uber and Airbnb belong to intermediaries which match supply and demand by pairing customers with the right suppliers of products, content or services, often by way of specialised algorithms. Because their impact on the local and international market shakes the existing market allocation mechanisms, such online platforms were defined by Riemer et al. (2015) as disruptive matchers.

Industries where matching was not organised effectively or efficiently previously, are a perfect breeding ground for these disruptive matchers. These might be industries with monopolised distribution channels. Airbnb is a prominent example. They only have 1.7 percent of the employee size of Marriott International, the world’s largest hotel chain, but more listed properties than the top five global hotel brands combined (Hartmans, 2017). By collecting the data on their users/visitors, online platforms can significantly increase their benefits. They can monetise this data by conducting analytical researches and selling or licensing the use of data to third parties. The Handbook on measuring digital trade (OECD, 2019a) defines intermediation fees that DIP (Digital Intermediation Platforms) accounts for the matching of customers and suppliers as:

Online fee-based intermediation services that enable transactions between multiple buyers and multiple sellers, without the intermediation platform taking economic ownership of the goods or rendering services that are being sold (intermediated).

The effect of the appearance of new, web-based intermediaries in the corporate sector is a clear shift of intermediation revenues and value added income from e.g. a travel agent (the traditional provider) to e.g. Booking.com (a web-based provider). These activities should be recorded in the national accounts via recording in the administrative register of the institution. This is certainly done for large-scale players and those that engage in transactions with other corporations. It is important to clarify that not the value of the transacted service itself (such as accommodation fees for hotel rooms or private accommodation rentals) is reported here. Only the margins or service fees charged for the intermediation are subject to recording in a register (Ahmad & Schreyer, 2016).

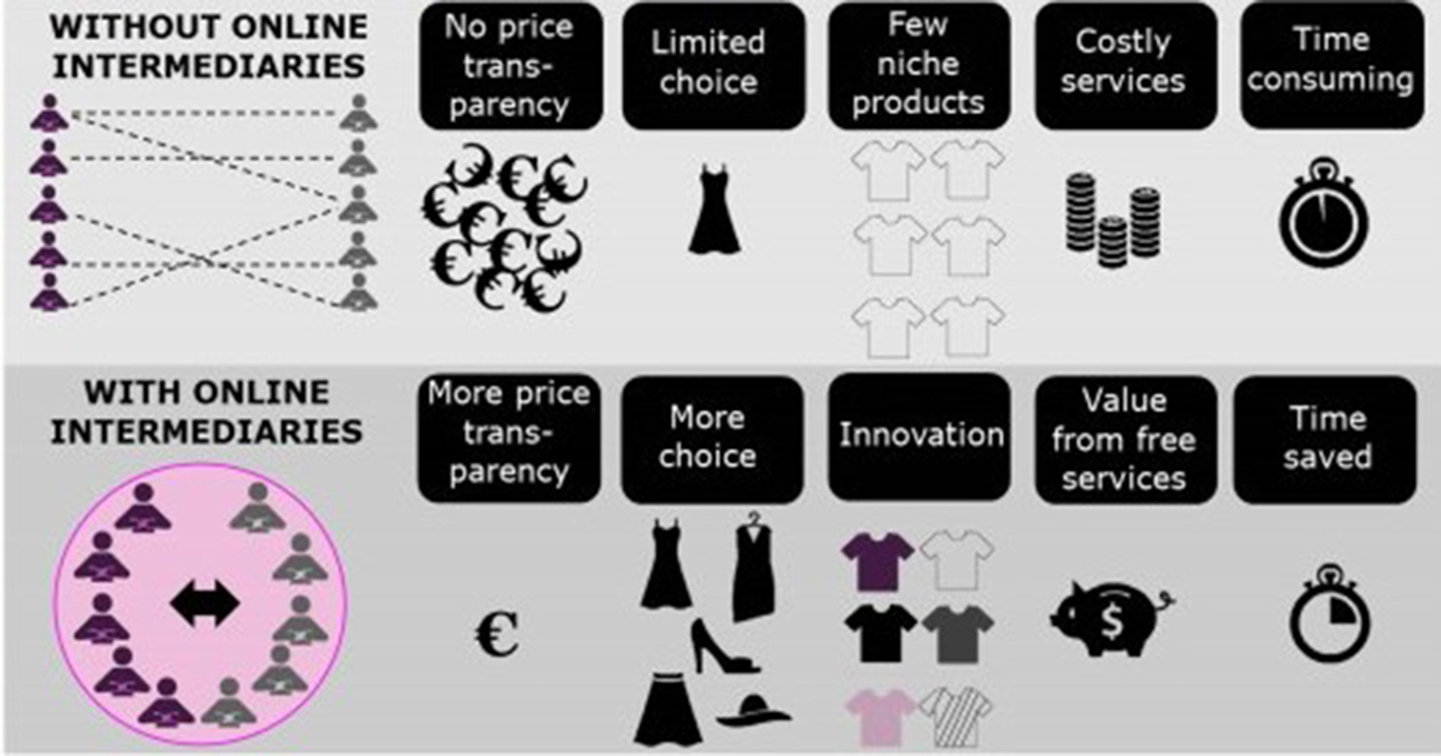

Due to the business model of online intermediaries, consumers benefit by having more price transparency and more choice as well as more insights in new products (innovation), save time and profit from the availability of free services. The research of Thelle et al. (2015) published by Copenhagen Economics, presented the consumption advantages of the digital intermediation platforms.

2.2 Consumption benefits from online intermediaries

Source: Copenhagen Economics

Digital intermediation of taxi services

Ride sharing and ride-hailing have been made available to a wider audience via high rates of adoption of internet services, smartphones with global navigation systems, online payment technologies, and advanced algorithms. Multi-sided platform business models are used by these services to attract both drivers and passengers. Communication, payment and feedback between the passengers and professional or non-professional drivers is enhanced via ride-sourcing services. Information is given to a passenger once a passenger specifies a destination. It concerns information about the possible route, estimated duration of the trip, the estimated or finalised price calculated by a dynamic pricing algorithm and the driver’s rating (OECD, 2018).

Ride-sharing companies have differentiated their service models to fulfil the requirements of various user groups, targeting high-end, mid-market and budget users separately. Uber, the largest ride-sharing platform globally, offers premium services through its service offerings such as Uber Black, Black SUVs and Uber Select. These services have specific characteristics, such as the use of high-end black cars and professional drivers and target the high net worth individuals and business customers.

Similarly, Lyft has premium brands (Lyft Lux, Lux Black and Lux Black XL). A driver with a qualifying vehicle can list his/her vehicle under those brands. As a consequence, the driver has the opportunity to gain a higher income. For the mid-market Uber has UberX and UberXL by which you can get an everyday ride at an affordable cost. Also, Lyft targets the mid-market through two brands: Lyft and Lyft XL. Again affordable prices targeting regular customers that are seeking convenience. Budget customers are also targeted by Uber and Lyft by the brands UberPool and Lyft Shared respectively. To reduce costs and be able to offer a cheaper rate to each customer, drivers cater to multiple customers at the same time that are sharing destinations close to each other (DBS, 2019).

2.3 Major ride-shares around the globe

Source: Mapchart, DBS

Database services

The world’s most valuable resource is no longer oil, but data (The Economist, print edition 6th May 2017).

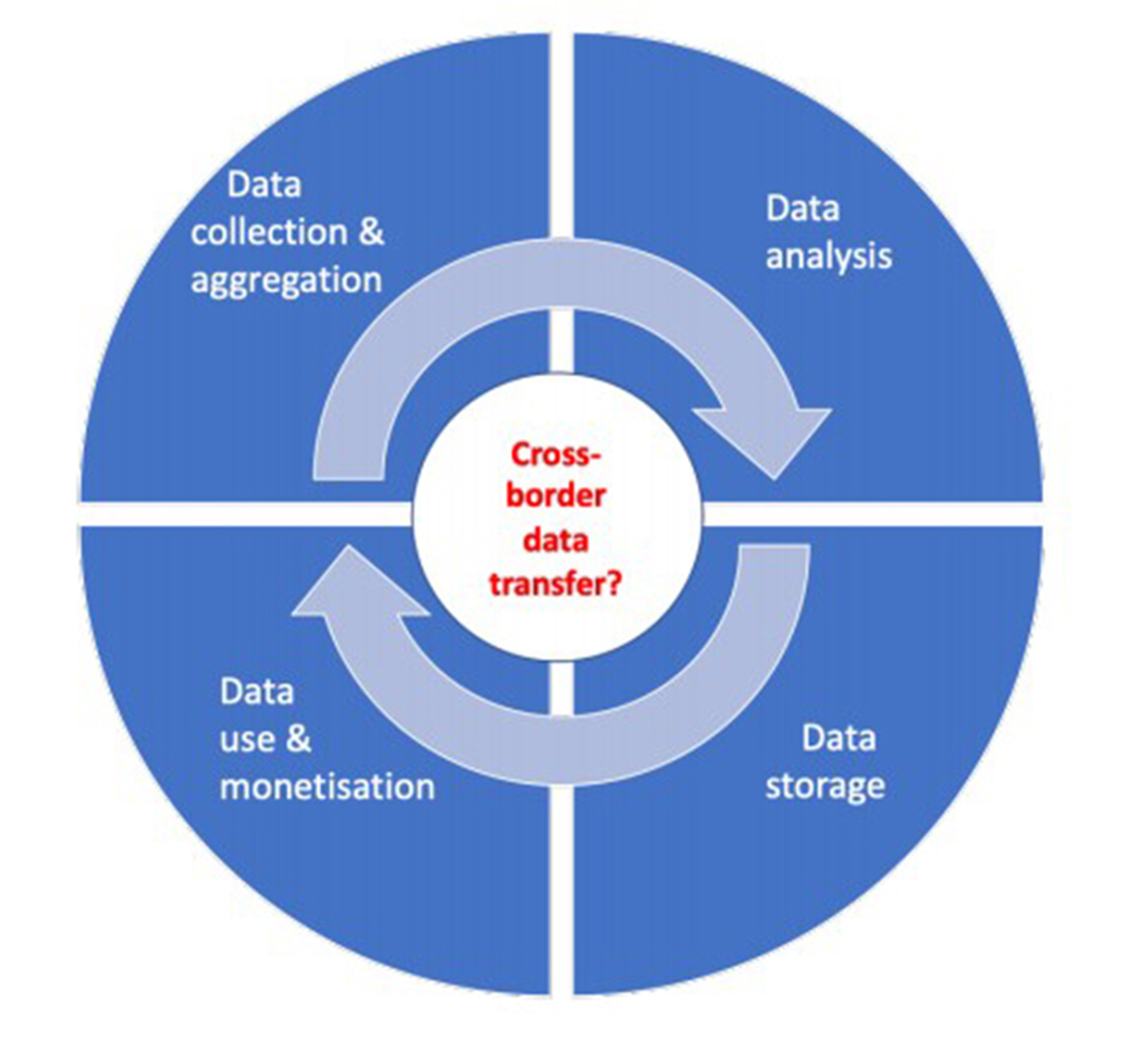

Our life becomes more and more driven by data. Recent years have seen an explosion in the generation of data, and the use of this data (e.g. organised in databases) in, for example, advertising-based business models. Managing the process of collection, aggregation, storage and analysis of data for the purpose of successful operation of business became one of the important parts of the daily activity of enterprises. However, because data is typically acquired for free, large parts of it (except those exchanges that are supported by an explicit payment, generally bundled in a different product) are de facto invisible in official statistics (except those exchanges that are supported by an explicit payment, generally bundled in a different product). Social networking sites such as Facebook, or search engines such as Google, offer "free" services to users in exchange for data that can be used by these firms to generate targeted advertising, and hence revenues (Nakamura et al., 2016).

2.4 The global data value cycle

Source: Nguyen & Paczos (2020)

Visconti (2019) define the data value chain by the following five stages: data creation and collection, data storage, data processing (data fusion and analytics), consumption (data visualisation and sharing), and monetisation (business model).

The SNA (OECD, IMF, Eurostat, 2008) provides a definition of databases that refers to data, without however, specifying what data is: databases consist of files of data organised in such a way as to permit resource-effective access and use of the data. Databases may be developed exclusively for own use or for sale as an entity or for sale by means of a licence to access the information contained.

Within the scope of this research, we apply the EBOPS definition of database services as: database conception, data storage, and the dissemination of data and databases (including directories and mailing lists), both online and through magnetic, optical or printed media and web search portals (encompassing search engine services that find Internet addresses for clients who input keyword queries). The CPC also designates a subcategory of databases as “original compilations of facts or information organised for retrieval and consultation, including mailing lists. These compilations are protectable in their presentation, but not their content”.

It is important to stress that cross-border transactions for data, such as software, cloud services, data storage etc. are of course already included in measures of international trade. In addition to these transactions, the transfer of property rights in respect of the above-mentioned products has also been measured within the framework of statistics on international trade in services. In addition to these transactions, the transfer of ownership rights with respect to above-mentioned products, also has to be measured under international trade in services statistics.

E-commerce

From the way we network, to the way we get our news – we are slowly but surely moving everything online. It does not come to a surprise that shopping is no exception.

In the past few decades, online shopping has gone from being non-existent to becoming a multibillion-dollar industry. Buying things online has become common practice among millions of people around the world. Recently the number of people buying goods and services online has increased more than ever before.

One of the reasons why online shopping has grown so much over the years is because of the experience that businesses are able to provide to their customers. We are constantly seeing businesses add new features and services for online shoppers, with the intent of providing them the same support and comfort that they would have during an in-person shopping experience.

Websites are the best-known form of e-commerce for companies which sell products online. Many consumers nowadays shop online, but companies can also be frequent customers of web shops. Even if the buyer does not pay electronically, sales via a website fall under e-commerce. It also does not matter which device a buyer uses to place his order: a desktop, laptop, tablet or smartphone. Consumers can also trade among themselves via websites. This type of e-commerce (C2C) is not measured in this research. In our research we focus on B2B and B2C e-commerce. A less well-known form of e-commerce runs via EDI: Electronic Data Interchange. This form only occurs in trade between companies. Business systems communicate with each other via EDI messages. This type of e-commerce is also taken into account in our research.

The OECD defines an e-commerce transaction as ‘the sale or purchase of goods or services, conducted over computer networks by methods specifically designed for the purpose of receiving or placing of orders. The goods or services are ordered by those methods, but the payment and the ultimate delivery of the goods or services do not have to be conducted online’ (OECD, 2011).

In 2013, more than one out of five Dutch companies sold electronically and more than half of them made purchases via e-commerce. Sales via a website are more common for Dutch businesses than sales via EDI. It seems that, over the years, online purchases and sales of Dutch companies have remained stable. In 2016, 26 percent of Dutch companies sold via e-commerce and 57 percent of them have reported online purchases of goods and services.

Both Dutch companies and Dutch consumers appear to have the same shopping pattern: they prefer to buy within their own country rather than abroad. In 2016, an average company bought for 92 percent of its web purchase value within the Netherlands. The remaining 8 percent of this amount refers to purchases from foreign companies: 6 percent from suppliers within the EU and 2 percent from online suppliers outside the EU (CBS, 2015). Dutch consumers followed the pattern of Dutch businesses. In 2016, only 7 percent of Dutch consumers bought online goods or services at foreign web shops (CBS, 2019). This trend was proven by OECD research (2014) which showed that in a majority of countries participated in the OECD investigation, the percentage of the enterprises that engaged in electronic sales in their own country was much higher than those who carried out cross-border e-sales.